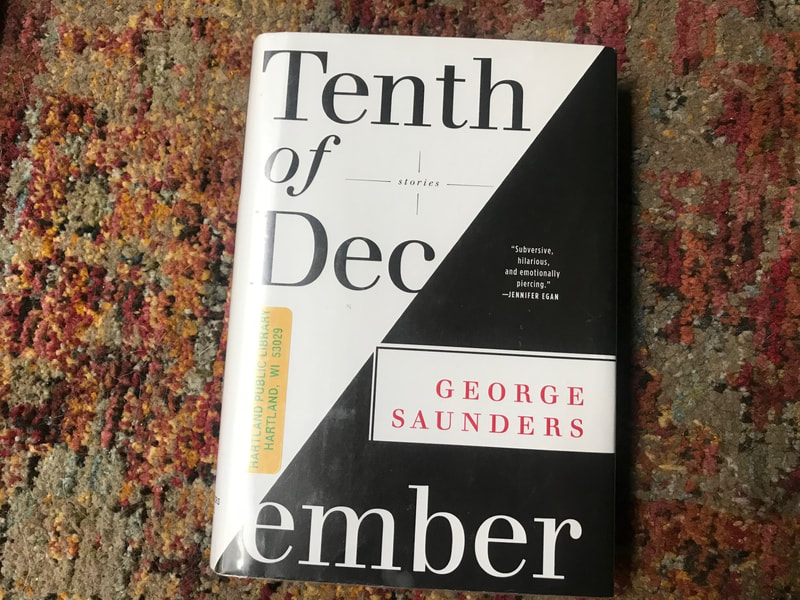

Several years back I worked with a guy whose wife was at the forefront of developing AI-type (artificial intelligence) writing programs. It sounded scary for my field as a journalist/reporter/writer. He described AI’s abilities (five years ago) in terms of writing simple stories and press releases. Input the data, set it loose. Then it turned out the product. Given the death knell for print journalists the past 30-40 years, as magazines evaporated and newspapers merged and slashed, AI sounded like another bell gonging to put our profession into the graveyard. That appears to have accelerated in recent months with AI grabbing headlines and investment gurus touting the abilities and life-changing effects of the technology. Technology has pretty much always leapfrogged with unintended consequences. Stuff happens that we can’t predict. Jobs go away. New ones are created. Some people decry the change. Others embrace it. AI will cover all those bases, and possibly more. What AI won’t do (most likely) is generate something new and original. It has to work from the inputs that it is given – the data programmed into it. It will imitate things that came before it. Humans have a different role. What we have to figure out, it seems to me, and the big question given the more repetitive actions AI can take over (even in intellectual and white collar work, like writing), is this: “What does this means humans should be DOING?” Where is our time valuably invested? If AI automation takes over, it pushes humans into another role. What’s it gonna be? We all need to work. We all also need to make money in our increasingly monetized world where wealth is incredibly centralized in smaller and smaller percentages of the population. The recent merging of the LIV-PGA golf tour is but one more example of how money rules and how those with wealth (and often dubious backgrounds) bankroll events and jobs. Will that become the model for humans in an AI-generation world? It will depend on those holding the wealth. Do those individuals care about the planet and the livelihoods of people in general or are they out to hoard their bucks and make sure they line the pockets of their other uber-wealthy buddies? There is a lot of anger and hurt in the world today trying to preserve things the way they were. That’s not the path as AI assaults us. Instead, using intelligence to grow the human species in terms of our roles as guardians (until some other species takes the top of the ladder) necessitates we look forward. What’s next? Where can AI help us and the world ecosphere develop in ways that utilize our skills and ENHANCE (not just preserve) the environment we rely on that allows us to exist physically? Those are the questions. Who answers them, and how they answer will determine our future. Who holds those reins? How much input will the little person have? I don’t know. But we’re going to find out. And, there’s gonna be a lot of chaos. Hopefully our curiosity and intellect and push to build and innovate – things that makes us human and different from other species – wins out. AI cannot duplicate that.  If you read a lot of books, how do you decide which ones to pick up next? There are many ways to choose, but have you found a reasonably accurate way to determine quality in the writer, plot, reporting, research, narrative? For a long time, it was a crapshoot for me. I listened to friends and respected their views and gave something they recommended a shot. Sometimes it would be like eating a perfect pizza and other times I’d spit it out like liver and onions. Book reviews you read from the experts are a bad idea. It took me years to figure that out. The simple reason is they are paid to review books, and that means for the most part they need to write a good review. They are skewed. Do you ever see a one-star review in the newspaper of a book that’s been reviewed? Nope. I wish I’d figured that out many years ago because it would have saved me a lot of wasted time reading novels that I struggled through, hoping to find those nuggets of worth the reviewer assured us were in there. Now, I discount all reviewers. If they give it a five-star, drop at least one of those stars off their rating, perhaps two. They are PR machines to promote the writer and their book – paid to make the author look good and sell their books. Remember that. When Google and Amazon came along, that seemed like a good thing – more populist. Still, you need to know how to use the tools they offer. Going mindlessly down their rabbit holes leaves you where you started. Every book is rated 4.3 (more or less) out of 5. Or so it seems. Very rare to find above a 4.5 ranking and similarly rare to find one below 4. Which means those ratings are padded. Friends of the author go online and write good stuff. Someone who hates the book occasionally adds their voice and drives the rating down, but that tends to be unusual. What about Oprah or Reese Witherspoon or other book clubs? While not experts, you can have some success picking up their recommendations if you know the type of material that gets you revved up. If not, then this becomes another useless enterprise. What’s come to me the past few years as I’ve honed my ability to sift through reviews and determine what ignites my curiosity and engages me page after page is averaging out the comments written in the Amazon review section and trusting our library people regarding top new choices they put in the front area (similar to trusting those reviews written by low-paid book loving employees at independent bookstores). Here's how my averaging system works. I challenge you to try it. Typically, the first several Amazon reviews are hot, five stars. Give them a quick glance. Determine which ones are BS and which are written from the heart. Get a sense of the plot, themes, intensity, what’s supposed to hold your attention. Know yourself. Know what you like, what bores you and what turns you off. Then head to the bad reviews, the one- or two-star reviews. Here’s where you get reality. People vent. You find out what’s horrible or doesn’t make sense or is petty. Whatever. Let this seep into your personal review brain. Average these good ones out with the bad ones and meld it into what you know about yourself – your likes and dislikes. WALLA! You have it. Your personal review system designed and catered to your reading style identified to select books most likely to hold your attention and have you make a recommendation. Next thing you know, you’ll be the sought-after reviewer.  When does intellect defeat instinct? Or, conversely, when does instinct win out? When you play senior baseball (or, if you remain physically active and competitive into your 60s), these questions come to mind. The reason they do is because so many players injure themselves trying to do things their bodies command them not to do. Your instincts tell you to run hard to first base. You do. You pull a groin muscle. A ball is hit to you in the outfield. You run and dive. You separate your shoulder. Done for the season. These things happen in senior baseball. Repeatedly. Bodies over the age of 55 don’t want to steam into second base and perform a pop-up slide. Your body wants to jog to second base (or lumber, or trot, pick your verb). But not sprint. In our league, over and over we see and hear of players getting injured as their instincts defeat their intellect. Your mind tells you to slow down. Instead, if you hit a slow roller to third base, you take off out of the batters box, presuming you can leg out an infield single. Instead, you tear your hamstring. There’s a friend of mine playing in one of these senior baseball leagues and he is currently out of commission with a groin pull. He tried to run too hard, more than his body could handle. When we recently discussed this, he said something to the effect, “I KNOW I shouldn’t have done that, but I just couldn’t stop myself.” He couldn’t overrule instinct with his mind. The innate desire to get to first base took over. Last season in our 55+ team, we got three new players to join us, all of them under the age of 60. Young bucks for the league. By the end of the season, all three were injured and unable to play. One tore his rotator cuff. Another pulled a groin muscle. And the third just generically messed up his arm so he couldn’t throw any more. When players join our team, they get positive reinforcement to NOT overdo it. DON’T sprint as fast as you can to first base. BE CAREFUL if you choose to dive for a ball. Slide into bases AT YOUR OWN RISK. The emphasis is on: “YOU COULD HURT YOURSELF!” The implication is you must analyze the situation, use your intellect, and not take risks that punish your body. As the three players from our team last year demonstrated though, it is much easier to SAY you’re going to slow down and be smart about your body than it is to actually play that way. You have to wonder if this goes back to neanderthal days when your senses had to be active and alarmed at all times to respond to predator threats. You had to go zero to a hundred at any time. Similar to baseball, where you are sedentary and suddenly you’re expected to explode to full speed. With age, you can’t physically do that anymore. Something has to give, and it’s usually a muscle, limb, tendon, ligament or bone. There are no answers to the instinct vs. intellect discussion. You can only work to engage your brain to still your body and hope the message gets through. Sometimes it does, but that’s when you get thrown out stealing second. |

Archives

June 2024

Categories |