I can’t find someone who doesn’t mock today’s weather reports. No matter where you go to find out what’s happening tomorrow or the rest of the week, whoever does the analyzing and reporting is mostly inaccurate.

Recently, I had a conversation with a friend on a side topic related to weather predicting. It’s the third time I’ve raised the issue with a friend about how the predictions for the next day or two evolves and becomes more and more distant in the future regarding rain or snow. For example, let’s say the weather person says it’s going to rain tomorrow. They give you a 63 percent chance for that to happen starting around 11 a.m. tomorrow.

Okay, got it. Maybe I need to change my plans.

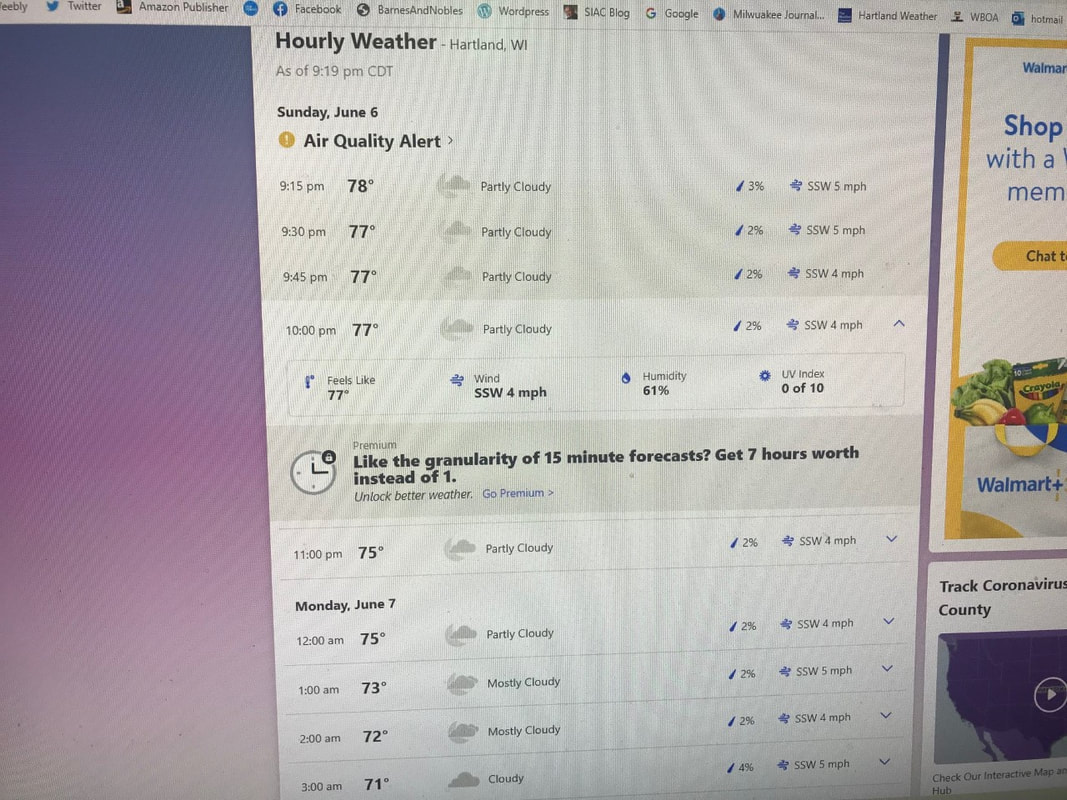

That report came out at 5 p.m. on a Monday, with the prediction for precipitation Tuesday morning. Before you go to bed that night, you check online for the hour-to-hour prediction on the weather web site, and find that the percentage for rain the next day is down to 54 and the rain won’t start until 1 p.m.

You go to bed thinking you might still want to play golf mid-morning. Or take a bike ride. Or whatever. You’re thinking though that the rain is still going to hammer you by mid-day Tuesday something.

You wake up Tuesday still thinking you might (or should) accomplish something outdoors. Your plans shouldn’t be banished, but you have a slight concern about the rain.

You go down to your desktop computer and pull up the weather site once again and check the hourlies. Of course, you now find that precipitation prediction is now down to 38 percent and it starts at 3 p.m. In addition, rather than the rate of rain rising as it had in the previous day’s posting, the hours of 4-6 p.m. having descending levels of 31 percent, 28 percent and 17 percent.

When you think of these numbers and calibrate them in your brain, what comes out? That it’s not going to f….cking rain all day. They give those numbers to CYA. “Hey, we gave you a possible percentage that it COULD rain,” would be the response from the on-air weather person if you ever had the opportunity to ply them with a cocktail and get to ask why they’re wrong so often.

This syndrome of bad weather predictions moving farther and farther off into the future until they disappear and no precipitation occurs seems to have reached epidemic proportions. Check it out in your part of the country the next time you’re looking a few days ahead at rain or snow. Test the theory and see if it holds.

Based on my conversations with these three friends, we all have seen a remarkable consistency to the growing displacement of storm clouds. Something’s going to come down. We don’t know when, and likely it’s going to be later than when the original prognosticators say it will. Go golfing. Who cares if you get wet?